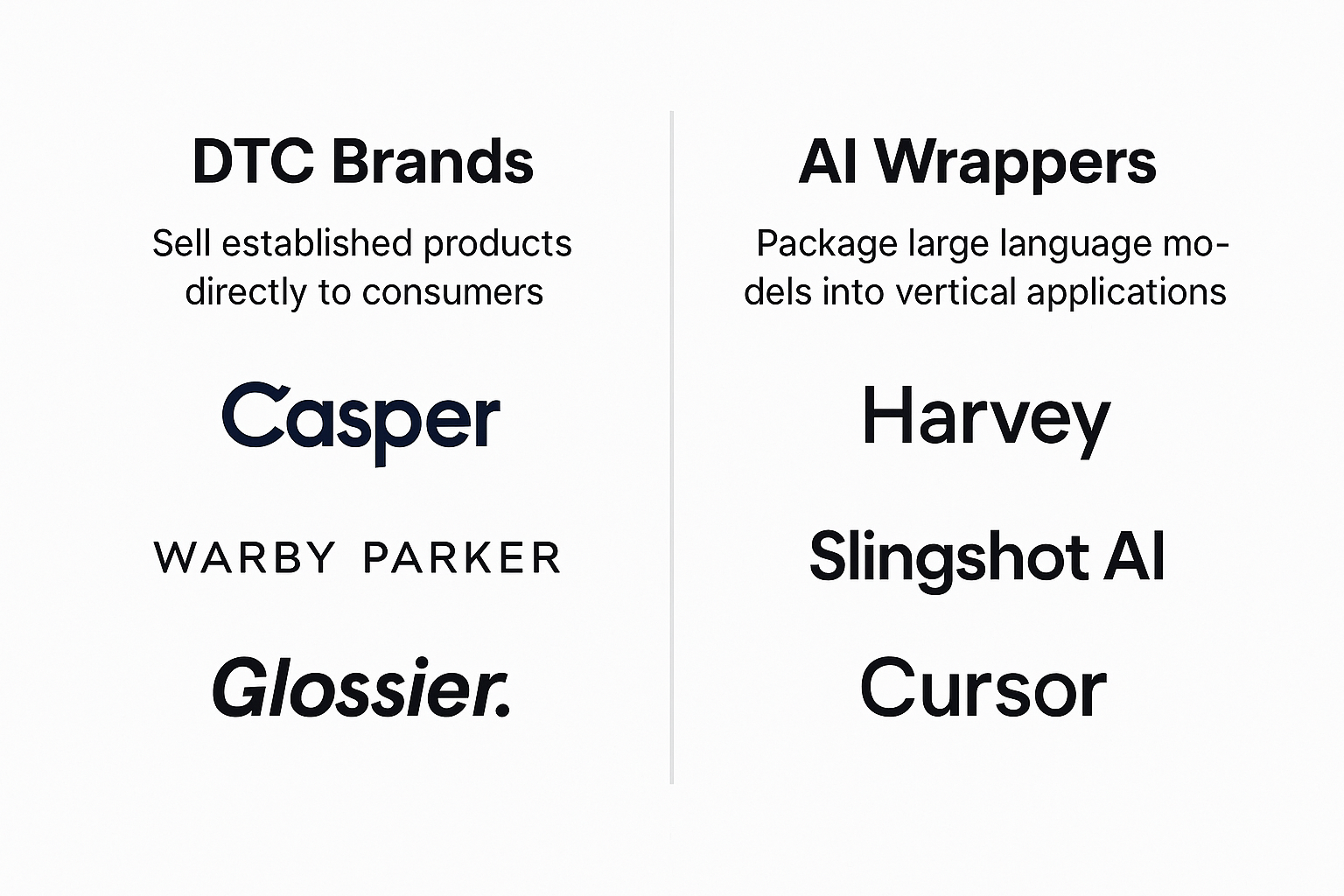

Over the last year, niche AI startups have exploded onto the scene. Companies like Slingshot (mental health), Harvey (legal), and Jasper (marketing), Cursor (code editor) are racing to stake out territory on top of large language models like ChatGPT and Gemini. At first glance, they feel innovative and differentiated. But if you squint, they look a lot like the early wave of direct-to-consumer (DTC) brands — Casper, Warby Parker, Glossier, Harry’s and Peloton — that disrupted incumbents not by reinventing the product, but by reshaping the story, distribution, and consumer experience.

I saw this firsthand at Casper. We weren’t reinventing the mattress — foam was foam — but we were reinventing the consumer experience and telling a story incumbents weren’t telling. We addressed a lot of the pain points in the legacy purchase experience (returns, trial, etc) with novel solutions.

The analogy here is hard to ignore.

The DTC Playbook vs. the Wrapper Playbook

- DTC brands didn’t invent new categories. Casper didn’t create mattresses. Warby Parker didn’t create eyeglasses. Harry didn’t create the razor. What they did was package the same products differently — through better storytelling, sleek direct-to-consumer distribution, and a brand that felt fresh.

- Wrappers in AI are doing the same. They aren’t building foundational models. They are packaging GPT-4 or Gemini into verticalized experiences — a chatbot for lawyers, a tutor for students, or a therapy bot for mental health. The innovation is in the brand, UX, Marketing, and trust layer, not the core technology.

Both movements promised a form of disintermediation: cutting out the retailer (in DTC’s case) or cutting out the generic chatbot like ChatGPT (in the wrappers’ case). And both attracted investors with the allure of scale and potentially better unit economics.

The Investor Story

In the early days, investors poured money into DTC brands on the assumption that direct distribution and savvy branding would create defensible moats. But cracks appeared quickly:

- Unit economics didn’t work (high CAC, low repeat rates). DTC brands showed strong gross margins but EBIT margins were often worse than the brands they were disrupting – showing the immense cost involved acquiring customers online.

- Low barriers via Shopify solutions meant dozens of mattress, glasses, and skincare clones flooded in.

- Retailers fought back with private labels and Amazon-level scale.

When I was at Blue Apron, I saw the same tension. There was incredible investor excitement early on — partnerships that popped the stock, bold new channel launches — but underneath it, the CAC and repeat dynamics were tough to overcome on the core subscription business once competition flooded in.

Today, wrapper companies face the same risks:

- Thin margins relying on API access to OpenAI/Anthropic.

- Low barriers to entry — anyone with a credit card and a developer can spin up a vertical chatbot.

- Foundational providers can move downstream and build their own verticalized products, just like Amazon Basics or retail private label undercut DTC.

The Incumbent Response

Retail giants didn’t just watch. Amazon, Walmart, Costco, and Target launched house brands and optimized shelf space to squeeze DTC. Meanwhile CAC costs for DTC brands skyrocketed as online ad prices increased. This tension led to many of these online brands showing strong topline growth at the expense of declining margins.

At Newell, I saw the flip side — how the large CPG’s thought about partnerships and private label strategy. When startups broke through, the response was fast and aggressive. We had the ability to compete aggressively by spinning up copycats, flooding the category with marketing, and using deep retail relationships to outmuscle the upstarts.

Foundational model providers could do the same. Imagine:

- OpenAI Legal Copilot in partnership with Microsoft

- Gemini Health

- Claude for Education

If these exist in a year or two, the wrappers look less like companies and more like features waiting to be absorbed.

The Future: Who Survives?

- Consolidation: Many wrapper companies will fade. A handful may endure as recognizable category brands, the way Warby Parker and Glossier still stand. But private market valuations of these DTC brands were mostly higher than where they are in the public markets – showing the challenges of rising CAC are hard to escape.

- M&A / Rollups: Incumbents in law, healthcare, and finance may buy wrappers to accelerate distribution or control a trusted experience. We saw this at the height of the DTC boom where large incumbents like Unilever paid 5x revenue for the DTC brand Dollar Shave Club. Years later they would wind down the business – showing that the economics just weren’t sustainable.

- Survivors win on trust, not tech: Just as Casper owned “better sleep,” a wrapper might own “the AI lawyer you trust” or “the AI doctor that feels safe.” But trust can be fleeting.

How Wrappers can Differentiate

1. BD Partnerships

- Just like in DTC, getting distribution right can be as important as the product.

- Wrappers can win by embedding inside incumbent platforms (EHRs in healthcare, CRMs in sales, LMSs in education).

- Moat = being where the customer already works, not asking them to switch.

2.) Trust and Brand

- In sensitive categories (mental health, finance, legal), brand credibility matters as much as accuracy.

- A startup that earns the “AI doctor you trust” badge through clinical validation could carve out defensible space. At Casper, we got endorsements from the American Chiropractic Association that actually helped lend credibility to the product.

3.) Proprietary Data & Feedback Loops

- Wrappers that capture unique proprietary datasets (e.g., anonymized medical transcripts, industry-specific transaction data) can fine-tune better than generic LLMs.

4.) Community and Network Effects

- Wrappers that build strong user communities (e.g., Jasper’s early marketer ecosystem) create defensibility beyond tech.

Wrappers survive if they move from being simply interfaces to becoming systems of record, trust, or workflow. If they don’t, they’re just nice brand sites waiting to be absorbed by OpenAI, Google, or incumbents in the space. The battleground won’t be who has the best model — OpenAI and Google already won that round. It will be who builds sticky, trusted, and resonant category experiences before the giants roll in.

Looking back, many of the DTC/BD distribution ideas I worked on — from Casper’s sleep telehealth concepts to Blue Apron’s fintech and subscription plays to Lime’s global partnership with Uber — were less about the product and more about building trust and a brand that resonated. That’s the same challenge wrappers face today.

DTC taught us that a brand story can win early, but scale wins eventually. Most wrappers will struggle to survive once the economics catch up. But a few may carve out lasting consumer trust and build enduring category-defining brands.

List of the Largest Wrapper Companies:

| Sector / Use Case | Wrapper Company | Highlight / Strength |

| Legal | Harvey | Deeply adopted by top law firms; legal research + drafting |

| Developer Tools | Anysphere (Cursor) | AI-native IDE; massive ARR, near $10B valuation |

| Enterprise Productivity | Glean | Cross-app search & knowledge integration for teams |

| AI Search & Answer Engine | Perplexity | Web-sourced, citation-backed, next-gen search |

| Narrative Intelligence | Blackbird.AI | Monitoring misinformation and reputational risk |

| Mental Health | Slingshot AI | Therapy/mental health focus; branded, domain-specific experience |