A VC once told me that 50% of some of their portfolio companies’ growth is coming through partnerships. I wasn’t surprised, but I found this quite interesting, because successful structure and execution seems to be the achilles heel of many organizations.

Through the marketing lens, there’s no shortage of content and advice on how to grow your startup. The thing is, most startups look at marketing as a cost center (which it usually is) but there is white space here that is more efficient than marketing and that is through partnerships. Now, I know “partnerships” is a broad term, but let’s try and narrow it down by focusing purely on revenue generating initiatives. In previous roles at Casper and Newell Brands, I oversaw numerous innovative partnerships and here are some lessons I learned as well as some thoughts on why this space continues to be undervalued.

Marketing Partnerships:

- Partnerships can help lower working marketing expenses by creating mutually reciprocal value exchanges. Oftentimes when we purchase advertising there are costs on two fronts (the paid media and the dollar discount or offer we may be using as a CTA – call to action). An alternative model that lowers CAC is to focus on a brand partnership with a non-competitor that shares a similar target customer. A simple example would be a furniture brand and a rental insurance company. Moving is a common trigger for both so is there an organic way to introduce your brand message into each other’s customer journey via a unique offer. Your brand gets additional eyeballs but doesn’t have to pay media CPM’s for it and because the two parties are complementary it feels more organic. The rental insurance provider gets to widen their base and target people who are likely moving. You could even take it one step further and offer to cover the customers newly bought furniture without raising their premium as a benefit. Creating discounts for nonprofits and trade organizations is another angle. AARP, AAA and the like, all have millions of members and these companies are constantly looking to offer additional value to their members. You could position your offer among this cohort. The other benefit of these types of programs, is that you can better insulate the brand from damage associated with constant discounting in the market as well as from retaliation from retailers that try to match pricing. If you are constantly running media with CTA’s involving a discount you have to be prepared for the brand risk involved and testing offers in closed wall ecosystems gives some protection here.

Benefit Incentive Partnerships:

- This is a good opportunity to try migrating away from cash discounts that you may be using and in exchange offer a value towards another service typically purchased in bulk to get efficiencies. A simple example is T-Mobile’s successful ‘Netflix on Us’ promotion which was also then quickly mirrored by Sprint and Hulu. The brand would purchase the subscriptions in bulk at a discount and bundle them with a purchase in lieu of offering a richer cash promo. Each business obviously has unique unit economics that may make programs like this cost prohibitive but the kinds of CAC we see in DTC startups today likely makes it feasible. Other examples here include offering airline miles with purchase (which can be bought in bulk for some cases for pennies on the dollar) or credit card offer programs.

Licensing Partnerships/Collaborations:

- These have been a mainstay of the fashion/entertainment world for many years and continue to be quite powerful. In 2011, the retailer Target struck a brand partnership with Italian fashion house Missoni which emptied the shelves and caused Target.com to crash all before noon the day of launch. In another space, they saw success in a home partnership with Michael Graves In the fashion world, one of the key decisions behind LVMH’s acquisition of luggage maker Rimowa was to create partnerships between the two companies. In January, they launched a new co-branded luggage collection. In late June, Gap launched a 10-year partnership with rapper Kayne West to develop a clothing line. Consideration consisted primarily of royalties and warrants in GAP. The announcement added $700 million to GAP’s market cap; that’s the power of partnerships. Collaborations have also helped struggling brands gain new life. Crocs was the only footwear company among the top 30 tracked by NPD that recorded growth in March of this year. Google searches reached a 15 year high and are now on Amazon’s Best Seller list. This is all a result of recent brand partnerships with singers like Post Malone, the Rock band Kiss and designers such as Vera Bradley and Balenciaga. The latter of which resulted in a 4.5 inch $850 platform Croc that within hours sold out. In the startup world, Casper’s product partnership with American Airlines and a sleep CBD gummy company all resulted in increased press and brand awareness. Even consider the opportunity to license the tech stack. If you’ve built a great piece of technology for your business, think about how it could serve others while also opening up an additional revenue stream. Gaming giant Epic Games, discovered that their Unreal Engine technology to make 3d graphics could also help a lot of other developers so they decided to license this out. This is a big driver behind the company’s massive valuation.

Product Development Partnerships:

- Sonos and Ikea came together to create a whole new product. Knowing that Millennials were downsizing and moving into urban areas, Ikea has adapted its merchandising strategy to appeal to smaller footprints. Why separate your audio products from your furniture when you can combine them. As a result the company created a line of hybrid speaker-home furnishing products from lamps to bookends. Ikea had exclusive rights to sell the product and Sonos lent their IP and product development prowess.

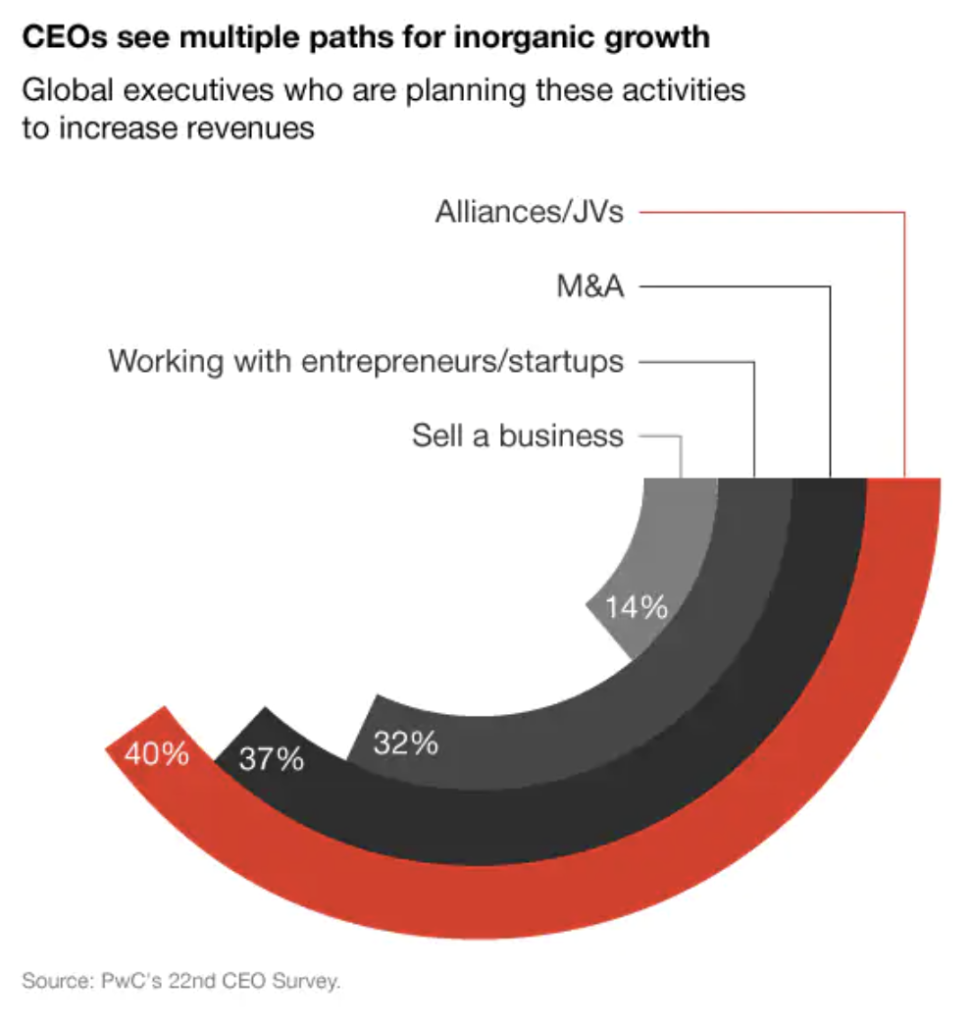

While this is just a small set of examples, there are hybrids of many more. Not all partnerships are worth the effort though (you don’t want to end up working on the next Cheetos Chapstick!) The key thing to realize is that brands need partnerships to grow. In PwC’s CEO survey, partnerships surpassed M&A in sources of growth.

Not all partnerships are worth the effort though (you don’t want to end up working on the next Cheetos lip balm!). In a future post I’ll discuss key points for a DPL as you craft common partnership agreements.

Part II: Structuring the Partnership – Key Points of the Deal

Crafting enterprise wide partnerships is really more art than science but having a strategy as you start to develop the structure sets it up for the best potential of success. For point of clarity, enterprise partnerships refer to company wide programs or initiatives that are typically multi-year, strategic opportunities, involving joint ventures, M&A, large commercial deals, licensing opportunities and the like.

When I first joined Casper to lead partnerships, the first thing employees would ask is what exactly does someone in my role do. Are you a business development person, are you in sales, legal, operations or corporate development? The reality is you need to likely have exposure to all these functions in order to be successful in the position and you need to take a strategy (often developed at the top) and build a roadmap on how to get there which could involve building in-house, buying or partnering.

At both Casper and Newell Brands we were constantly approached by 3rd parties who wanted to enter into partnerships with us on various fronts (marketing, commercial, etc) and the organization was spending significant amounts of energy trying to prioritize which ones to tackle. I opted to create a systematic approach moving forward to evaluate these inbounds.

Before I begin any partnership discussion, I spend time understanding more about the other party’s business. This can be as simple as having informal discussions about how they operate to also looking at any public commentary on their industry and any projections for where things are headed. This gives me a macro perspective on what might be sticking points or objectives if we work together. As an example, at Newell Brands, I was negotiating a large media deal for one of our brands who had a celebrity athlete who was embarking on a rock climbing tour to raise money for local charities. Our marketing team wanted to bring the tour to life, but also didn’t want to just run ads and create a one-sided story. Knowing that publishers are interested in engaging content that they can monetize as well as new revenue streams, I created a content licensing/hybrid media deal whereby the tour was brought to life using the publishers audience thereby giving us reach, and in return, we allowed them to monetize the experience by selling ads to non-competitors. Win-win. In another case, we were developing a physical product to track sleep but couldn’t get the cogs (cost of goods) to work out. Furthermore, we grappled internally over who would own the data and would we charge for the service. Knowing the ongoing sensitivity and risks to owning consumer data we explored partnerships whereby the other party would subsidize cogs in return for us licensing the (opt-in) data. The reason why I crafted the deal this way was because I knew the counter party was in the business of selling data to insurance companies and therefore was more valuable to them than us. Our weakness revolved around the inability to successfully mine the data like the other party so we were realistic about our weakness and found a way to focus on areas that we do best (i.e. product development, marketing).

Another element to understand is how your counterpart ranks in seniority as well as their role within the company. Everyone needs a chance to prove themselves but if you feel early on that you are getting the run-around from the other party and they are having to ask multiple departments in a matrixed organization for feedback, be prepared for a potentially bumpy ride. I’ve started negotiations with savvy business development leads that went smoothly and I’ve also started with others that fell apart. I find that if you can’t find a champion on the other side it will be very difficult to get anything done; if their boss doesn’t see the value (or priorities shifted) you can face an uphill battle. I was negotiating a unique licensing/co-marketing partnership with a large US appliance company and began discussions with their marketing team who, while having good intentions, only felt comfortable staying in their ‘lane.” Large matrix organizations are slow – plain and simple. And most functional teams have salaries (and often bonuses) tied to how they perform, so there isn’t always a clear incentive for them to help drive the initiative past the finish line if it involves other departments. I often respond to these dynamics by trying to show how the overall effort will make them look like a rockstar through internal/external PR and secondly, will hopefully add to the topline. That said, It takes someone who has the same objective and goals; they have to see and be able to express the same vision you share. If you’re getting the run-around, it’s sometimes better to part ways early.

Once you’ve had proactive high level discussions with the other party about what a tie-up could look like, I then take a page out of Amazon’s playbook and begin by writing a dummy press release announcing the effort. This helps me articulate the main objective as well as think through the benefits on both sides and ideally happens before you get into any tactical discussions with the other party. In the absence of putting pen to paper here, you can quickly lose sight of the end goal as you get into negotiations. The second thing I do is put together a list of give’s and get’s. This outlines what we are able to ‘give’ in the relationship and secondly what we expect to ‘get.” This is another great visual way to see if the needs are balanced or if you have a one sided deal. I’ve found many times that when I thought a proposal was fair in my head, after completing this list, it really wasn’t.

At this point, I put together a hot sheet with all the pertinent facts of the deal. This is one document containing all the pertinent details and is designed to be shared among cross functional areas for feedback. It’s a bad idea to get into negotiations and find out that other internal parties on your end want something else or aren’t aligned. This document gets everything on paper related to the objectives so that you don’t have to go into discussions and then try and change the deal terms in the 11th hour. Internal politics has derailed many last minute deals; it’s not fair to the other party and can hurt the chances for success.

The Actual Agreement: Points to Consider

- How will IP be split / will there be licensing agreements / what are fair rev share terms. Back them up with facts or comps from other industries or sectors.

- Exit options/liquidated damages provision – sometimes things don’t go as planned and I’ve had a couple agreements where we couldn’t uphold our end of the bargain and had to execute this clause. It hurts, yes, but you know your quantum upfront. And if one party is shouldering a lot of upfront costs, this can hopefully make them more amenable.

- Reps & warranties/indemnification – while standard in most agreements, in certain vice or regulatory opaque industries it’s especially important to think through how risk will be mitigated. Will either party have to take out additional insurance: who will shoulder the premium or will it be split. Oftentimes the buyer will expect the seller to cover this, but I’ve also been in a situation where we split it 50/50. In some situations both parties can’t come to agreement on reps & warranties; it’s worth considering r&r insurance to take some of the exposure off the table. On a $10m deal for example, insurance can run ~$200K; fairly affordable for peace of mind especially if both parties agree to split the cost.

- Revenue share agreements / earn-outs or performance guarantees – be very detailed on the economics of the deal (I even use hypothetical examples in the appendix of the agreement for point of clarity) – cadence of reporting, invoicing, waterfall obligations if you have a rev-share with a recoup component.

- Data sharing/audit rights – If you are both sharing (or gaining) customers and/or data from the partnership who ultimately owns the end relationship. If you’re creating a joint product development effort, which party is going to sell it? If you’re both trying to sell the same product, who is managing customer service? In my experience having two parties jointly selling a collaborative product can lead to customer experience issues that need to be clearly ironed out prior to developing a go-to-market strategy. This is the benefit of a licensing strategy – keep the commercial opportunity tied to one party. Sonos’ partnership with Ikea is an example of not stepping on each other’s toes (Sonos lends IP and Ikea provides distribution (sales).

- ROFR’s/ROFO – I’ve asked for in some agreements (and not in others). It’s worth considering in a situation where you know you’re in a position that will make you the partner’s biggest customer or supplier. If a ROFR doesn’t pass muster with the other party, consider a ROFO; this at least helps keep you from getting blindsided. If those two don’t work, try asking for a MFN (most favored nation) clause. This may accomplish what the party is going after but be less restrictive. In some partnerships that might morph into M&A, one party will sometimes ask for a ROFR on the ability to match an investment from another entity – this could present some signaling risk and turn away interested investors from the deal knowing that what they offer could be matched. I suggest striking ROFR’s as it relates to M&A for this reason. If one side really pushes protection to execute a potential investment consider warrants or other derivatives.

- Terms & Renewals – Most of the time the larger partner (or party with the greater resources) will want a shorter term agreement and the smaller partner will want longer. It’s a big risk for small companies to execute these deals. In some cases, the smaller party might even use the deal as proof of concept to their investors (if they are backed by VC for example) and will even staff up accordingly to support. Therefore, there is substantial risk that smaller parties undertake to do deals thus justifying their focus on getting the longest term feasible. Term length is unique to each deal (ideally 1 year being the max) but it’s fair for either party to ask for liquidated damages as a result of breaking the agreement for reasons other than cause; this can provide some protection to the party that was arguably more exposed in the deal. As it relates to automatic renewals; I’m not a fan – best to strike this.

- Exclusivity – This is something almost one party in each negotiation will ask for (and then the other side will want to make it mutual). If this is a deal breaker for the other party considering tightening the competitive set you’ve included or specifying particular products/channels. Be prepared to commit to a revenue target, a total contract value or other metrics if you expect the other side to agree, especially if you are cutting off potential customer(s) who could be a significant percent of their business.

- Lawyers – attorneys advise on legal risk, you shoulder the business threat. I spend a lot of time working with internal and external counsel in crafting partnerships and have found some attorneys can add tremendous value while others are too risk averse or have a myopic perspective. I find it’s very helpful to walk them through your thinking before providing them the DPL to draw up the contract. One last note on lawyers – if your partner is smaller, they may not have in-house counsel; thus they will have to hire an outside firm to consult. This can quickly become quite expensive with numerous back and forth drafts which is even more of a reason to get all the key business elements of the deal ironed out first.

Last thing to note is that not all partnerships will be successful; In fact many will not be worth the squeeze. In my experience they fail because one party didn’t uphold their end of the bargain or because they weren’t a match from the get go. This is ultimately a relationship so it’s important to treat others as you’d want to be treated and it goes without saying, but communicate, communicate, communicate. Be open about your intentions and what is most important to you. I’ve watched some people negotiate as if it’s a form of brinkmanship and they feel their credibility is tied to the outcome. Take the high road and play fair. The key is gaining mutual alignment on the objectives and focus on the other parties interest not positions when you get into negotiating the deal structure.

3 comments on “Partnerships Are Your Hidden Weapon”

Jareed….Well written article on the untapped potential of creative partnerships to increase revenue, save budget, and increase marketing effectiveness….Stephen Markow

Great callouts. I have a startup, and we’ve always struggled to build successful partnerships like this. I will use these tactics.

[…] written before on best practices for brands looking to build growth partnerships (here, and here). This post is not about mechanics. It’s about utilizing technology to help frame […]