If you have a startup and you’re venture backed, then you ultimately need an exit. Historically, this has been through M&A or by going public. However, with the exception of some SaaS deals, there’s not been a lot of M&A activity recently in the consumer space. Strategic buyers often feel many startups are overvalued and aren’t interested in paying the premiums. The alternative is an IPO and there’s a lot of new innovation to look forward to here. Earlier this year, there was growing support for direct listings among some high profile VC’s, namely Bill Gurley, who felt many startups were leaving “money on the table” by going through a traditional IPO. Slack and Spotify are two examples of companies that have done direct listings. His argument is that in a traditional IPO the bankers engineer the deal to get a pop for their institutional clients and ultimately the company doesn’t get to keep any of the upside. Case in point is Snowflake (SNOW) that went public yesterday via a traditional listing. The stock jumped 111% on the first day and as a result left $3.8b on the table. The downside with doing a direct listing has been the inability to raise capital as has been the case in a traditional IPO. That said, the NYSE has been working with the SEC on a way to do a primary raise concurrently with a direct listing that was recently approved but has since been rescinded as other parties pushed back. More to come here.

Category: Corporations

Investing in airlines has never made sense. As Warren Buffet once said “if a far-sighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favor by shooting Orville down.” Buffet never liked airline stocks, but did see a possible entry point after years of consolidation to make an investment in Delta which he followed through on. That’s now a distant memory as Berkshire recently cashed out their holding following the pandemic. It’s for this reason that you haven’t, and won’t, see startups getting into the airline business; it’s too competitive and capital intensive with meager margins to make the business attractive to growth stage investors. But you are seeing aviation tech on the fringes of the industry attract VC money. Jetblue Technology Ventures, for example, has made numerous investments in the travel sector.

A landmark case against Uber and Lyft is playing out in California courts that could fundamentally challenge their business model. Proposition AB5 would require companies like Lyft and Uber to reclassify their drivers from independent contractors, as they are today, to employees. As a result, both companies have threatened to pull out of California altogether as they simply cannot comply with the ruling. Their business model isn’t built for that structure. The economics of ride hailing don’t contemplate having W2 employees. If this was the case, fare’s would rise substantially across the board, and demand would likely fall. That said, they are already preparing to lose this fight and this will require a radically different approach to how their business functions moving forward. It’s been surmised that they will pivot to a franchise model whereby independent franchisees will license the ride hailing companies software as well as brand IP while making drivers now regular employees. If you think this is a step backwards, you’re right. Under this model, you’ll end up with potentially thousands of black car and taxi companies using the software. This is exactly how the model existed before the Uber’s of the world came around and, I’m afraid, won’t even address the larger issue.

It’s true innovation when a business builds something for themselves and then realizes there’s a potential application beyond internal needs.

Take, for example, a company like Apple that started predominantly as a hardware company making computers and other peripherals. Years later, when they created the App store it was originally conceptualized as a platform to deliver programs directly developed by Apple. But they realized that there was a much bigger opportunity here to create a marketplace model and the App store of today was born. In 2019, this line of Apple’s business contributed over a half a trillion dollars in billings and further reinforces the stickiness of their hardware business. If Apple had kept this ecosystem truly closed for fear of losing control, then their market penetration would be significantly less.

As tech companies descended on Capitol Hill this week, the ongoing debate around antitrust continues. Startups have long lamented about the anticompetitive business practices adopted by the big 4: Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Google. If you build a business that relies on the Apple or Google app stores then you automatically know you’re going to pay a ~30% toll to access consumers. The debate has further been heightened as some startups like Classpass have been hit with this toll as they roll out virtual classes due to COVID. The founders argue that they are forgoing their normal take rate from providers (gym’s, etc) they work with during COVID so why is Apple charging them 30%. Apple is in an interesting situation, because if they make exceptions for one business, they need to make for others. They also would face potential legal battles from previous customers that did have to pay.

A recent report claims $TWTR is considering a subscription model to augment a significant decline in advertising revenue. This would be among the first of the big social media companies to consider this approach and I believe could lead to a reckoning in the industry. $FB is currently facing a backlash among advertisers who claim the social media company isn’t doing enough to control controversial rhetoric on its platform and will inevitably see a decline in advertising revenue. A few years ago, the idea of paying to access online “news” content wasn’t a thing. Publishers were primarily in the business of selling ads in offline media and as they built their online presence they carried this business model over. As consumers got irritated with intrusive ads, it became clear they had to change their offering. Newspapers such as the NYTimes piloted new paywall programs to test consumers’ appetite for subscription based products. The result was mostly favorable, and as a result, many publishers today have pivoted their business models to favor subscription over advertising revenue especially as it becomes increasingly difficult to get ad dollars from brands in a world in which the big tech companies ($GOOG, $FB, etc) dwarf smaller publishers in traffic.

I’ve always had a strong viewpoint that digitally native vertical brands are a dime a dozen and those who will have successful exits are the ones who are vertically integrated, own manufacturing, strong defensible positions and/or are durable/consumable businesses built on recurring revenue and more enticing LTV metrics. With the recent news on Lululemon acquiring Mirror for $500 million it proves there is still an appetite for strategic buyers to pay premiums for DTC startups. In this case, I estimate LULU paid 5x-6X revenue which is a phenomenal outcome for the founders and investors. LULU was already a minority investor in the company which gave them intel into the business that other competitors likely didn’t get. Why corporate VC gets a bad rap sometimes, a good strategic investor can bring a lot of value.

A VC once told me that 50% of some of their portfolio companies’ growth is coming through partnerships. I wasn’t surprised, but I found this quite interesting, because successful structure and execution seems to be the achilles heel of many organizations.

Through the marketing lens, there’s no shortage of content and advice on how to grow your startup. The thing is, most startups look at marketing as a cost center (which it usually is) but there is white space here that is more efficient than marketing and that is through partnerships. Now, I know “partnerships” is a broad term, but let’s try and narrow it down by focusing purely on revenue generating initiatives. In previous roles at Casper and Newell Brands, I oversaw numerous innovative partnerships and here are some lessons I learned as well as some thoughts on why this space continues to be undervalued.

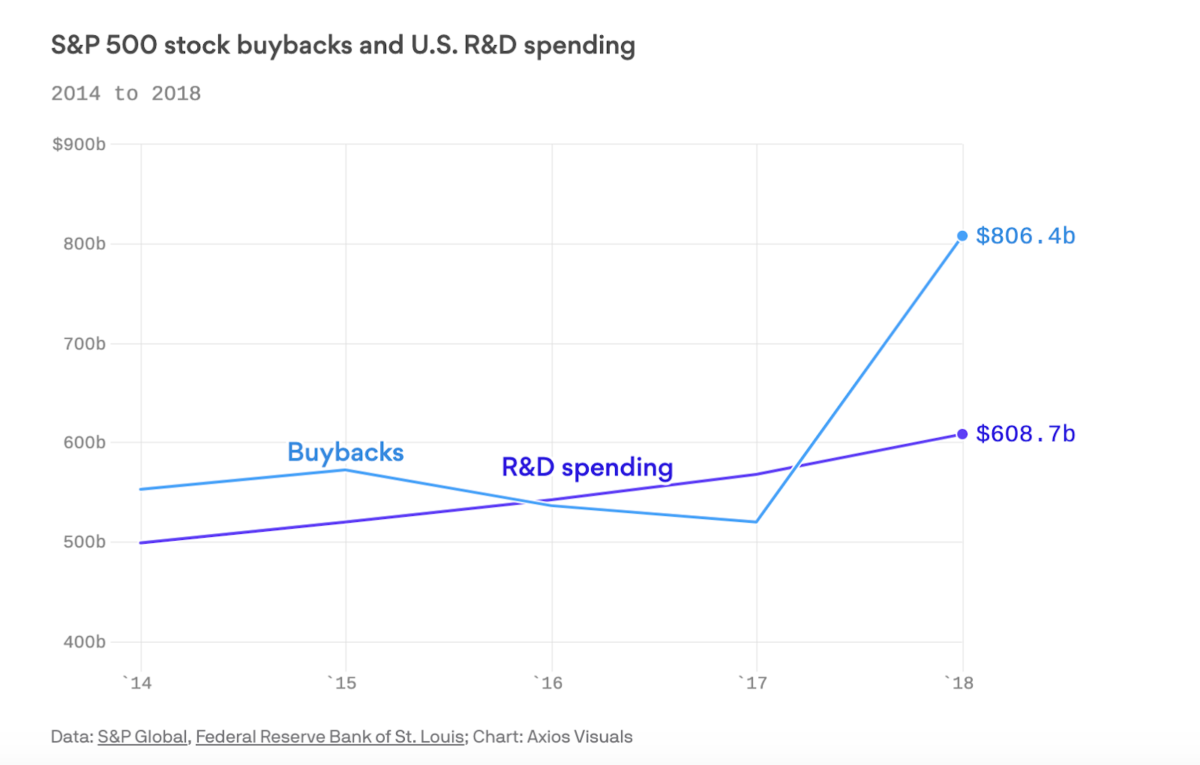

Less than half of the S&P 500 invest any money in R&D. Instead, they are pumping dollars into stock buybacks that ultimately provide no real tangible value to the productivity of the enterprise (sorry Warren). I’m convinced this is stifling innovation and giving startups more room to eat their lunch. Wall Street has no patience when it comes to waiting around to see innovation bare fruit which can sometimes take 4+ years. The unfortunate reality of this is management must then live by a quarter-to-quarter clock which hurts internal innovation. This myopic perspective is further reinforced by hedge funds and activist investors who are chasing short term gains. Allocators of capital need to recognize that management has to be given more leeway to invest for the long run. If they don’t, a heavily funded lean startup will be glad to take their customers.